| Minor League Classic "Doubledays" vs. "Cartwrights" |

|

|

|

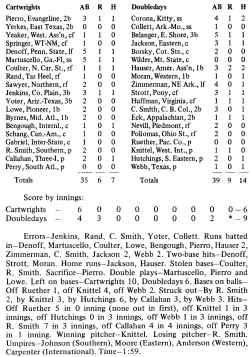

By Ed Brooks In Cooperstown, N.Y., on July 9, 1939, the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues conducted its celebration of baseball's centennial. A brief announcement in the March 2 edition of The Sporting News outlined what was to be the minor leagues' part in the 100th anniversary observance. The program was to consist of the dedication of a research library, the unveiling of several bronze tablets memorializing outstanding minor league personalities and an all-star game. Inasmuch as the all-star game was to be the centerpiece of the day's activities, it is the purpose here to trace the evolution of that event from conception to conclusion and to offer some thoughts as to why the game failed to achieve all that was anticipated, thus making it an all-but-forgotten episode in the history of baseball. Furthermore, its imperfect outcome may suggest something as to why the minor leagues' presence at Cooperstown has been all but invisible. Each of the 41 leagues in the National Association, according to The Sporting News article, would be requested to select one player. From this anticipated "galaxy of stars," two clubs would be organized and meet at Doubleday Field. George Trautman, chairman of the minors' Executive Committee, was to be in charge of the entire program. The July 9 date was chosen because it was two days prior to the major league All-Star Game in New York City. It was felt that this conjunction of the two games would "enable thousands of executives and fans to attend both functions." What seemed like a good idea proved to be an unfortunate choice. Alas, in the months that followed, a combination of circumstances turned the Cooperstown game into a symbolic ritual at best and, at worst, a failure not worth repeating. A competitive contest did not result, and what might have become an annual and exciting event with much ensuing publicity for the minor leagues had instead become a memory for only a few. Trautman's call for players brought responses that were tardy and mixed. A review shows that when the players convened at Cooperstown 17 leagues had not sent a player representative. These were the Arizona-Texas, Arkansas-Missouri, Bi-State, Cape Breton Colliery, Cotton States, East Texas, Evangeline, Georgia-Florida, Kitty, Mountain State, Northern, Piedmont, Sally, Texas, Western, Western International and West Texas-New Mexico. To fill the gaps in the ranks, local sources were tapped. For example, additional players from the Canadian-American League were used. Eddie Sawyer, a Can-Am manager, "represented" the Northern League, while two other Can-Am managers, Elmer Yoter and Amby McConnell, played for the Arizona-Texas and Bi-State leagues, respectively. Other appointments were made from the ranks of outstanding semi-pros and collegians in Central New York. What caused the failure of the anticipated result: a "galaxy of stars"? Trautman's request for players went unheeded in part because each league president had his own conception of the occasion and there was no way of enforcing the directive. In their defense, league presidents had several legitimate reasons for ignoring Trautman's plea or for their half-hearted responses. Small rosters in the lower minors created the prospect of either playing short-handed for several days or signing a free agent. It would be difficult or impossible to persuade a club owner to do the former and, from both a talent and financial viewpoint, not feasible to do the latter. This, of course, would always have been a problem in planning for a minor league all-star game. Clubs certainly could hardly be faulted for not wanting to risk the loss of a star performer in the midst of a pennant race. Perhaps Texas League President J. Alvin Gardner spoke for all when he said: I would like to name a player for the game, but it would mean the man selected to the team would have to lose a week or more of play and I don't think it fair to the team or fans to snd away a star for that length of time. The contribution of the Texas League was to send a uniform. Even this modest gesture was useless because special uniforms were furnished for the game. Another pragmatic problem must be considered. The expense of sending a representative had to be borne by each league. Despite popular misconceptions manifest today, the economy in 1939 had not been restored to a level of prosperity, and many struggling minor league circuits, especially those far from Cooperstown, might deem such a cost unbearable or, at best, frivolous. Planning and coordination left something to be desired. This contributed to the result. The game date conflicted with league all-star games which were scheduled about the same time. In fact, the East Texas League contest was played on the same date, July 9. Scheduling the game a month after the Hall of Fame's formal dedication and induction ceremonies may have made the minor's celebration seem anticlimactic. Dan Daniel was unintentionally prophetic when, writing about the dedication and induction ceremonies in The Sporting News, he declared: "Cooperstown has had its big day of 1939." Slating the minors' game close to the major league All-Star contest also may have diverted attention from, rather than attracting attention to, the former. Finally, lack of publicity probably had an effect. After the March announcement, The Sporting News made editorial mention of the occasion just once, and it was not until the June 22 edition that the first player designations were announced. This was hardly designed to draw national attention to the event. Some of the "players" sent by leagues that did participate were symbolic of their lack of interest and genuine commitment. They responded to the letter of Trautman's request but not to the spirit. As mentioned earlier, the Texas League sent a uniform. The Pacific Coast League was represented by old Dutch Ruether, who happened to be on a scouting trip for the Los Angeles club. For his dismal performance, see the box score. The American Association sent Joe Hauser, a really big name in minor league history, but a manager of a semi-pro club in Sheboygan that summer. The International League "player" was Benny Bengough, Newark coach. The Southern Association sent veteran Bob Smith, who appeared only briefly with Chattanooga in 1939. Although the Can-Am League helped out with additional personnel, its official representative was Ottawa manager Wally Schang. All of these were good names, but certainly no "galaxy of stars." Many of the lower minors responded in the spirit intended. Even so, the Inter-State League representative had a season average of .207 in 25 games, and Bill Denoff of the Penn State Association was not active in 1939. There was a brighter side to many league selections. Butch Moran, Lucien Belanger, Ray Zimmerman, Joe Callahan, Johnny Hutchings, Walt Lowe and Art Strott were all having good years, and Warren Huffman hit .415 for Staunton in the Virginia League. Many others were certainly legitimate league representatives. Perhaps there is significance in the fact that of all those participating only Hutchings and Callahan later appeared in the major leagues. And only Moran would come close to being labeled a minor league star. Umpire appointments were most appropriate. Bill Carpenter, Ollie Anderson, Steamboat Johnson and Charley Moore had a total of 123 years' experience. Managers were two minor league institutions. Mike Kelley handled the "Doubledays" with Knotty Lee his coach. Spencer Abbott managed the "Cartwrights," assisted by Larry Gilbert. The ceremonies aspects of the National Association's day at Cooperstown were nicely planned and apparently well executed. As reported in The Sporting News of July 13, the festivities began with the dedication of the library and the presentation by Trautman of 400 appropriate items for its shelves. Instead of the originally anticipated several bronze tablets, one was unveiled which was dedicated to the seven founders of the National Association. Two of them, John Farrell and T. J. Hickey, were present. The library has become indispensable for researchers, but few are aware of the occasion of its dedication. Thus the tablet is the only direct physical evidence that there was once a minor league day at Cooperstown. Still, to one who holds the minor leagues in high esteem, it is the game itself which disappoints. Despite the presence of some bona fide stars, the game seemed to have all the intensity of an old-timers' game and was no more significant than the exhibition played annually at Cooperstown since 1940 by two major league clubs. The first and last National Association all-star game, the birth and death of a novel idea which might have become an annual event, marks the only significant involvement of the minor leagues in Hall of Fame activities and the beginning of major league dominance. It is not totally inappropriate to suggest that the multiplicity of factors which resulted in the failure to produce a genuine minor showcase event may have led to the onset of long-term trends at Cooperstown. Surely, the Hall of Fame since 1939 has provided little recognition of the minor leagues in its activities or in its exhibits. In an editorial in the April 27, 1939, edition of The Sporting News, publisher Taylor Spink made a comment apropos of this view. In recommending Tim Murnane and Mike Sexton for the intended bronze plaques, Spink said in part: So far, the names nominated to the Hall of Fame have a decidedly major league tinge. None whose career has been almost completely bound up with the minors has been proposed. Yet the minors have played as important a part in the propagation of the game as have the majors and should have their niche at Cooperstown. He continued: "If the minors are to be given places in the Hall of Fame - and there is no valid reason why they should not - then they could make no better start than by selecting their No. 1 and No. 2 distinguished figures - Mike Sexton and Tim Murnane." The names of Murnane and Sexton were among the seven included on the bronze tablet, but Spink's larger hope remains unfulfilled. Before continuing, stress should be given to the reflections of an observer of the day's events. Dick Conners covered the ceremonies for The Sporting News. A long-time correspondent for that paper, the former Albany baseball writer and "Voice of Hawkins Stadium" in the New York capital is now New York State Assemblyman Richard Conners. Amid telephone calls, quick conferences, the signing of correspondence and all of the other manifold duties and activities of an Assemblyman's office, a delightful, wide-ranging discussion was experienced during which Conners offered significant insights into the entire event and the game specifically. In his report in The Sporting News he had called the league representation the "sole disappointment" of the day. During the interview he placed primary emphasis on the economic factor which prohibited struggling minor leagues from financing the expenses of a player. The Assemblyman mentioned speaking earlier in the 1939 season with an Eastern League player who foresaw this financial problem. Despite the sense of disappointment he still feels, Conners continues to remember the event as "a gigantic thing, even awesome," considering the number of leagues that were represented from across the country. Here, then, is a view that emphasizes a failure of the times rather than of the concept or its execution. Conners believes that an annual minor league all-star game at any time would have been logistically and financially impossible. In any event, the minor leagues did have their day in Cooperstown and if July 9, 1939 is not one of the more memorable days in the history of baseball, it should be remembered as an occasion when, at least once, acknowledgement was made that professional baseball is also minor league baseball and recognition should be given thereto. Here is the box score of the game: |

Doubledays vs Cartwrights

Doubledays vs Cartwrights