| The Great American Baseball Trivia Sting |

|

|

|

ROBERT E. SHIPLEY

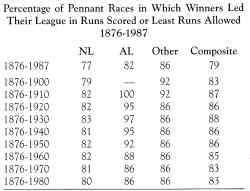

How to make friends, influence people, suffer no bores, and learn important baseball facts without ever having to look them up. An unusual statistic unveiled. THE OBJECTIVE: To set up and execute a well-deserved sting operation against the perfectly obnoxious baseball trivia bore of your choice. The Mark: Any insufferable acquaintance who insists on torturing the entire world with constant, meaningless baseball minutiae. I am not talking about the average enthusiastic baseball fan, but about the person who seems to gain feelings of superiority by learning and then expounding on every boring and trivial detail of the game. You know the type well. His/her last conversation with you probably began with "What was the highest fielding average ever achieved by a third baseman using a Wilson glove?" For the purposes of this demonstration we will refer to the deserving mark as "Insufferable." We will also assume that the individual is male, even though this is not a prerequisite. The Set-Up: You approach Insufferable with a sporting proposition to prove that, contrary to his own opinion, anyone can learn to become a baseball trivia expert with a minimum amount of effort. After deciding on an appropriate wager -perhaps for Insufferable to avoid all talk of trivia for a month - you suggest the following rules: 1. Only one question will be used to decide the bet. (As you will see, you can liberalize this rule later to your own advantage.) 2. The subject of the question will be limited to guessing the pennant winner for any major league pennant race since 1876. 3. Insufferable gets to select the contestant. 4. You will be allowed one minute before the contest to pass your secret formula for trivia success along to the contestant. 5. The contestant will be allowed to ask two questions (clues) and will be given two chances to guess the pennant winner based on the answers to the clues. Obviously, the clues cannot be any variation of: "Which teams were in the World Series that year?" or "Which team had the best won-lost record?", etc. The Sting: You arrive at the appointed time to discover that Insufferable has selected his cousin Larchmont as the contestant. Although you fully expected Insufferable to choose, perhaps, a five-year-old child or someone in a coma, the selection of Larchmont does appear to go beyond the bounds of fair play. Insufferable is justifiably smug - secure in the knowledge that Larchmont once thought the Bronx Bombers were a group of terrorists from New York City. Your work is cut out for you. Larchmont sits as if in a trance, preoccupied with adjusting his favorite red paisley bow tie and picking dried spaghetti sauce off his Madras shirt. With great trepidation you take him aside to whisper your secret instructions. He seems to understand, but who knows? The game begins. Opening his Total Baseball with a Cheshire grin, Insufferable decides to go for a merciless kill. "Larchmont, old buddy, name the pennant winner in the Union Association in 1884." Eyes rolling toward the ceiling, Larchmont slowly forms the first question that you imparted to him. "Which team led the league in runs scored that year?" The grin quickly disappears from Insufferable's face. In barely audible tones he replies, "St. Louis." "Then St. Louis was the pennant winner," Larchmont says matter-of-factly. Insufferable's silence tells the whole story. Larchmont claps his hands in glee, knocking his glass of iced tea into his shoe. He seems not to notice. With growing rage, Insufferable demands another chance - double or nothing. Graciously, you consent. No fool, Insufferable searches for a pennant winner that did not lead the league in runs scored. The silence is broken only by the sound of flipping pages and of Larchmont absent-mindedly squishing iced tea in and out of his toes. Finally: "Which team won the National League pennant in 1966?" Without hesitation Larchmont counters, "Which team led the league in runs scored?" "Atlanta." "Then Atlanta was the winner." "Wrong! Wrong! Wrong!" Insufferable shouts in triumph. "He gets another clue," you remind. "No problem," Insufferable replies, his confidence restored. Larchmont pauses to remember the second question. Finally he blurts out, "Which team gave up the fewest runs in the league that year?" Insufferable answers by slamming the hook shut and storming from the room. Opening the discarded volume to officially confirm the outcome, you tell the confused cousin, "Los Angeles, Larchmont. Los Angeles gave up the fewest runs." "Then, Los Angeles was the pennant winner." "Precisely." Why The Sting Works: While not 100 percent foolproof, the league leaders in runs scored and least runs allowed (opponent runs) are the two most powerful historical predictors of pennant success. Between 1876 and 1987, 50.2 percent of all pennant races were won by the team that led the league in runs scored. Thus the contestant has a one-in-two chance of deriving the right answer after the first clue. In 79 percent of the pennant races during the same period, the pennant winner either was first in runs scored or in least runs allowed. Hence, in eight out of ten contests, the contestant will be able to guess the pennant winner after two clues. As shown in the table below, your chances for success improve the more unscrupulous Insufferable is. For example, he is more likely to pick pennant races in the more distant past to avoid lucky guesses based on general knowledge of current events. Unfortunately for him, these two predictors were even more powerful before 1980. (While not shown, these predictors succeed only 37.5 percent of the time from 1980-1987.) Or, if Insufferable tries to confuse the issue by turning to one of the past major leagues other than the National and American Leagues (i.e., Union Association, American Association, Player's League, or the Federal League) your chances for success are improved to no worse than 86 percent (92 percent for the 19th century). This table also suggests refinements to the sting which you may want to attempt to improve your chances of success, For example, if Insufferable is agreeable, you could limit your universe to pre-1940 American League pennants, thus giving yourself no less than a 95 percent chance of success. Of course, you could even try to limit the contest to pre-1910 American League pennants, where the chance of success is 100 percent. But I am sure you would not want to take advantage - good sport that you are! Robert E. Shipley is a systems analyst for the Department of Defense in Philadelphia. |

The Great American Trivia Sting

The Great American Trivia Sting